Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly disrupted social life worldwide, cutting off many of the vital connections forged in what sociologist Ray Oldenburg famously called “third places”—those informal gathering spots separate from home (first place) and work (second place). Third places such as cafés, parks, libraries, and community centers have historically nurtured community bonding, social engagement, and wellbeing.

As the world transitions to a post-pandemic reality, the importance of rebuilding and reimagining third places has become urgent. These spaces are integral not only for social interaction but also for mental health recovery, community resilience, and the evolving hybrid lifestyles that blur boundaries between work, life, and leisure. This article explores the evolution, challenges, and innovative design strategies for third places in the post-pandemic era, highlighting examples, impacts, and future directions shaping the social fabric of modern cities and neighborhoods.

Background and Evolution of Third Places

Third places have long formed the backbone of vibrant communities. Ray Oldenburg introduced the concept in his 1989 book The Great Good Place, emphasizing that such spaces foster relaxed social interaction, democratize community life, and provide “neutral ground” where people can gather informally, build social capital, and nurture identity. Classic third places include pubs, coffeehouses, barbershops, bookstores, parks, and community centers.

Over recent decades, third places faced decline due to several factors:

- Growing suburbanization prioritized private housing and car-oriented lifestyles.

- The rise of shopping malls and online commerce displaced traditional communal spots.

- Digital technologies shifted socialization increasingly into virtual realms.

- Urban gentrification and redevelopment often displaced locally rooted third places.

The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic deepened this challenge by forcing closures, social distancing, and heightened caution about shared spaces. Overnight, many third places shuttered or saw dramatically reduced foot traffic, severing crucial social connections and sparking widespread loneliness and community disintegration.

Post-Pandemic Changes and Response

Following initial lockdowns and restrictions, communities experienced a gradual but uneven return to third place usage. Key trends emerged:

- Reduced and cautious usage: Early reopening saw tempered visits, with many retaining health precautions, limiting capacity, or gravitating to outdoor spaces.

- Adaptation to new norms: Spaces incorporated physical distancing, touchless technologies, enhanced cleaning, and ventilation improvements.

- Rise of outdoor and semi-outdoor venues: Parks, plazas, rooftop gardens, and pop-up dining areas flourished as safer, more flexible social environments.

- Hybrid social models: Use of virtual third places alongside physical ones gained traction, with online communities complementing in-person gathering.

- Community resilience: Grassroots efforts and informal initiatives revived local social networks, employing flexible, bottom-up approaches.

Encouragingly, research and observation indicate strong public desire to reconnect in third places, underscoring their vital role in social healing and urban vitality, though full recovery remains a work in progress.

Design Strategies for Post-Pandemic Third Places

Designing third places in today’s context requires rethinking flexibility, inclusivity, and integration with socio-environmental realities. Successful approaches include:

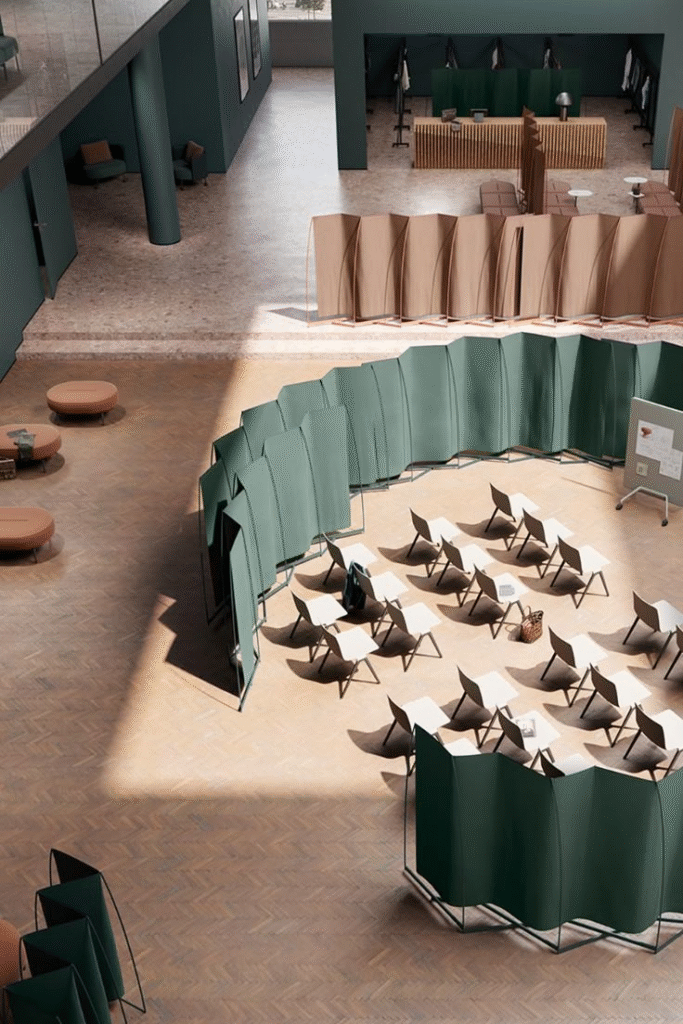

- Flexibility and adaptability: Modular furniture and movable partitions allow spaces to shift between solo work, small meetings, and social gatherings easily.

- Indoor-outdoor integration: Encouraging seamless flow between interior lounges and sheltered outdoor areas extends usage irrespective of weather and enhances safety.

- Zoning for diverse needs: Creating quiet corners, collaborative hubs, and open lounges accommodates varying privacy preferences and activities.

- Technology integration: Reliable Wi-Fi, power access, and booking platforms facilitate usage management and hybrid connectivity.

- Safety and accessibility: Thoughtful lighting, clear wayfinding, and socially distanced layouts foster security and broad inclusion.

- Blurring boundaries: Designing third places that support both work-related and leisurely functions recognizes the fusion of life spheres in hybrid lifestyles.

These principles support vibrant, resilient, and user-centric third places capable of adapting to public health challenges and evolving social norms.

Case Studies and Illustrative Examples

- Seattle University’s Jim and Janet Sinegal Center: Features flexible indoor-outdoor spaces fostering casual interaction, quiet study, and interdisciplinary collaboration in a campus context.

- Revival of community hubs in Sri Lanka and Malaysia: Informal, multi-activity social venues capitalized on outdoor spaces, localized programming, and cultural consonance to reignite social life.

- Flexible office-based third places: Tech campuses and coworking providers revamped lounges, pop-up cafés, and rooftop decks into amenity-rich environments for hybrid workers.

- Urban placemaking projects: Initiatives like Houston’s Discovery Green transformed underutilized spaces into vibrant social and event venues, catalyzing neighborhood revitalization.

- Neighborhood-level interventions: Pop-up markets, shared gardens, and community centers function as anchors in rebuilding social cohesion and fostering inclusivity.

These case studies highlight how intentional design, layered programming, and community involvement drive successful third places post-pandemic.

Benefits of Reinvigorated Third Places

- Enhanced social connection: Facilitating interpersonal engagement alleviates loneliness and isolation intensified by the pandemic.

- Mental health support: Informal gathering spaces promote relaxation, stress relief, and emotional restoration.

- Support for hybrid lifestyles: Third places bridge between home and office, accommodating remote and flexible working arrangements.

- Community identity and cohesion: Frequented local venues nurture belonging, pride, and shared narratives.

- Stimulation of creativity and innovation: Chance encounters and collaborative zones catalyze idea exchange and social vitality.

- Public health resilience: Quality outdoor and semi-open spaces provide safe alternatives reducing transmission risks.

By reestablishing third places, cities and neighborhoods strengthen their social infrastructure essential to collective wellbeing.

Challenges and Considerations

- Health and safety balance: Designing spaces that feel welcoming while respecting ongoing infectious disease precautions requires innovation.

- Avoidance of over-commercialization: Maintaining affordability, accessibility, and genuine community focus counters gentrification risks.

- Equity and inclusion: Ensuring diverse populations have meaningful access and representation in third places mitigates marginalization.

- Privacy and trust: Incorporating technology necessitates transparency around data use and respect for user autonomy.

- Sustaining engagement: Active programming, responsive management, and community ownership are vital to keep third places vibrant.

- Environmental conditions: Climate adaptability, weather protection, and infrastructure investment challenge seamless use across seasons.

Careful balancing of these factors supports resilient, equitable third place ecosystems.

Future Outlook

Looking ahead, third places will increasingly:

- Fuse physical and digital experiences: Augmented reality, virtual gathering spaces, and blended social platforms will complement physical venues.

- Prioritize wellness and sustainability: Incorporation of biophilic design, green infrastructure, and health-promoting elements will become standard.

- Evolve through co-creation: Communities will drive design and programming via participatory models enabled by digital engagement tools.

- Expand networks and clusters: Linking multiple third places across neighborhood and city scales will create richer social ecosystems.

- Leverage technology: Smart scheduling, analytics, and immersive media will enhance user experience and operational efficiency.

- Benefit from supportive policy: Urban planning, zoning reforms, and public investments will underpin the proliferation and preservation of quality third places.

These trajectories promise to deepen the social, cultural, and economic fabric of cities in the hybrid, post-pandemic world.

Conclusion

Post-pandemic third places are more essential than ever, embodying the spaces where community, creativity, and care flourish beyond the confines of home and office. Through sensitive design, thoughtful programming, and inclusive governance, these spaces can heal social rifts, promote hybrid work-life balance, and anchor resilient neighborhoods.

The future of third places embraces adaptability, connectivity, and diversity, fostering human wellbeing and vibrant public life in a rapidly changing urban landscape. Reinvesting in third places is not just a spatial challenge but a profound social imperative—to rebuild the “great good places” that enliven our lives and communities.

For personalized guidance and expertise on designing and activating post-pandemic third places that enrich social connection and urban vitality, please reach out:

Mishul Gupta

Email: contact@mishulgupta.com

Phone: +91 94675 99688

Website: www.mishulgupta.com