Introduction: Rediscovering Roots in Modern Skylines

In the relentless march of urbanization and globalization, traditional architectural diversity has often given way to homogenous, industrial-style buildings. Yet a powerful resurgence is underway: the incorporation of indigenous architectural principles into modern urban developments. This revival is not mere nostalgia but a pragmatic response to pressing environmental, social, and cultural challenges.

Indigenous architectural traditions, deeply embedded in the interplay of climate, community, and cultural identity, offer sustainable, resilient, and meaningful frameworks for building living environments in global cities. This blog post explores the resurgence of these time-honored practices, how they are adapted through modern science and technology, and their transformative potential in shaping ecologically sound, socially cohesive, and culturally vibrant urban spaces.

Indigenous Architecture: A Holistic Nexus of Ecology, Culture, and Community

Indigenous architecture refers to vernacular building traditions developed by native populations over centuries in intimate dialogue with their environment and social systems. It embodies a design philosophy that seamlessly integrates functional utility, cultural symbolism, and environmental harmony.

Key Characteristics Include:

- Climate Adaptability: Indigenous building methods optimize ventilation, thermal mass, shade, and rainfall management tailored to local conditions. Thick earthen walls regulate temperature, while steeply pitched roofs facilitate water runoff in tropical zones.

- Sustainable Material Use: Locally sourced bamboo, mud, stone, and timber minimize transportation emissions and harmonize with ecosystems. Such materials often exhibit biodegradability and are renewable.

- Community-Centered Design: Structures prioritize social interaction, privacy, and traditional functions, reflecting familial and tribal organization.

- Spiritual and Symbolic Elements: Architectural forms and ornamentations represent cosmological beliefs and societal hierarchies, anchoring identity.

These elements collectively foster buildings that are resilient, resource-efficient, and inherently tied to cultural meaning.

Highly respected Indigenous architect Louise Gardiner observes, “Indigenous design offers more than aesthetics; it is a framework for living responsibly within our environment and communities.”

The Drivers of Reviving Indigenous Architectural Practices

Environmental Considerations

Modern urban centers grapple with overheating, flooding, pollution, and resource scarcity—the very challenges indigenous architecture was designed to mitigate. Reviving these methods enables passive design strategies that reduce reliance on mechanical systems, lowering both carbon footprints and running costs.

For example, the use of courtyard designs promotes cross ventilation, mitigating urban heat island effects. Indigenous water harvesting techniques in housing reduce runoff and urban flooding.

Cultural Resilience and Identity

Cities face risks of cultural erosion as migration and modernization reshape demographics. Incorporating local architectural vocabularies strengthens cultural continuity and communal belonging. It fosters spaces where residents feel reflected, improving mental and social wellbeing.

Māori architect Bernadette Ehatahi emphasizes, “Architecture rooted in indigenous knowledge lifts up community values and strengthens identity amid rapid urban change.”

Social & Economic Benefits

Local material sourcing and traditional craftsmanship support regional economies and preserve artisanship. This approach democratizes opportunities beyond high-tech construction, embracing social inclusion and circular economies.

Skilled indigenous laborers not only build structures but also transmit knowledge through apprenticeships, ensuring cultural continuity and empowering communities.

Climate Change Resilience

With changing weather patterns and disasters increasing, indigenous architecture’s adaptive strategies—like flexible walls, modular extensions, flood-resistant foundations—offer valuable blueprints for urban resilience.

Integrating Indigenous Wisdom into Contemporary Urban Design

Reviving Vernacular Forms in Modern Contexts

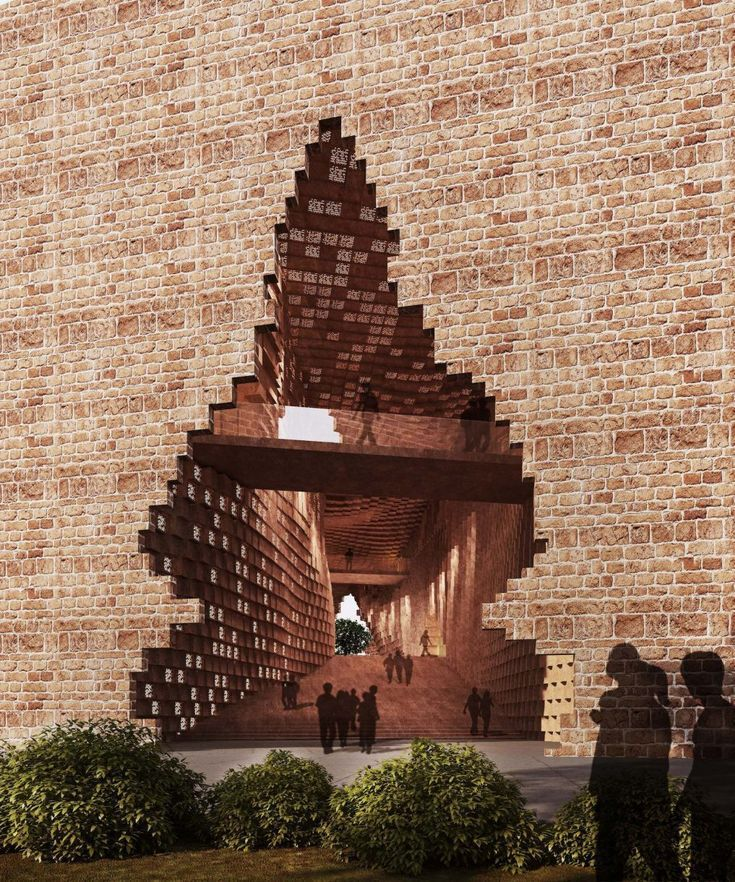

Urban planners and architects increasingly incorporate indigenous features: the jaali lattice screens of India and the mashrabiya of the Middle East are reinvented in facades to optimize ventilation and daylight while enhancing privacy.

Courtyards are reintroduced into apartment layouts, offering microclimates, social hubs, and plantscaping opportunities. Sloped roofs and large overhangs manage water and shade in metropolitan contexts, maintaining cultural continuity while addressing modern needs.

Material Innovation: Balancing Tradition and Modernity

Traditional materials like compressed earth, adobe, and bamboo are combined with reinforced concrete or steel to meet seismic and fire codes. Natural plasters are infused with water repellents to extend longevity without losing breathability.

Use of locally adapted hybrid materials reduces environmental impacts and enhances structural performance.

Community-Led Design Processes

Successful indigenous architectural revivals hinge on actively involving indigenous communities, local artisans, and residents in design decisions. This collaborative approach protects cultural integrity and fosters ownership.

Governments and developers are increasingly engaging indigenous knowledge bearers to co-create culturally sensitive, environmentally responsible urban spaces.

Policy and Governance

Encouraging indigenous architecture requires supportive policies and incentives: zoning laws that allow traditional spatial layouts, tax breaks for using local materials, and heritage preservation ordinances that protect vernacular neighborhoods.

Certification programs recognizing sustainable construction rooted in indigenous methods are emerging, incentivizing developers and buyers alike.

Organizations like the International Union of Architects are championing indigenous architectural rights and integrating them into international sustainable development goals.

Global Perspectives: Diverse Examples of Revitalization

India

Ahmedabad’s housing projects reflect an integration of jaali facades and passive cooling courtyards, alongside modern amenities. Rooftop terraces host medicinal plant gardens revitalizing traditional knowledge in city life.

Latin America

Bogotá and Mexico City have seen urban developments that weave indigenous stone masonry and courtyard planning into high-density housing—a blend of modern engineering and pre-Hispanic spatial concepts fostering community and climate resilience.

Australia and New Zealand

Collaborations with Aboriginal and Maori communities have produced culturally resonant housing that respects ancestral land ties, uses traditional timber framing, and incorporates indigenous landscaping principles.

Africa

In Cape Town and other urban centers, vernacular roofing techniques and natural ventilation systems rooted in tribal knowledge improve urban housing comfort and durability, marrying tradition with necessity.

Overcoming Challenges in Reviving Indigenous Architecture

- Regulatory Frameworks: Many building codes favor industrial standards and materials, complicating the use of traditional methods.

- Risk of Tokenism: Without genuine community involvement, indigenous elements may be superficially applied, diluting cultural significance.

- Skill Erosion: Urban migration contributes to the loss of traditional building knowledge; training programs are crucial.

- Economic Constraints: Sometimes indigenous methods appear costly or labor-intensive compared to mass production.

Addressing these requires holistic approaches combining education, policy reform, economic incentives, and cultural respect.

The Future: Fusing Tradition with Innovation for Sustainable Cities

The path forward lies in hybrid methodologies embracing the best of indigenous wisdom and modern technologies—prefabrication, digital fabrication, material science, and green building certifications.

Urban planners and architects envision cities where heritage vernacular styles dictate sustainable spatial configurations, natural cooling, and energy efficiency, while meeting the livability standards of the 21st century.

Community resilience, cultural vitality, and ecological sensitivity are embedded into the urban fabric, making cities both places to live and repositories of living heritage.

Conclusion

Reviving indigenous architectural practices in urban development offers more than aesthetic or nostalgic value—it is an imperative for sustainable, resilient, and culturally vibrant cities. It challenges architects, planners, and policymakers to rethink urban visions, embracing a pluralistic approach that values traditional knowledge alongside innovation.

As cities grow and climate challenges intensify, indigenous architecture provides time-tested lessons and pathways for urban spaces that nurture people, culture, and planet. The future of architecture is grounded not just in steel and concrete but in the profound roots of human place-making.

Contact:

Mishul Gupta

Email: contact@mishulgupta.com

Phone: +91 94675 99688

Website: www.mishulgupta.com